Transitional pterosaurs – the links no longer missing

digital drawings, 2022–2025; all artwork by Freddi Spindler

see more pterosaurs / Petrodactyle is another pterosaur in the Lauer Foundation

The Late Jurassic limestones of the Franconian Alb, widely known to preserve the Solnhofen Archipelago, are among the most diverse and detailed areas to study pterosaurs. For a very long time, each of the many fossils could be assigned either to the more primitive and long-tailed “rhamphorhynchoids” and the more derived short-tailed pterodactyloids. Since the pterodactyls were not known from older layers than the Later Jurassic but flourished throughout the entire Cretaceous – when long-tailed pterosaurs did not exist anymore – this transition must have happened in the Middle Jurassic. Just like the origin of pterosaurs as a whole, this most important step within their evolutionary history remained unknown.

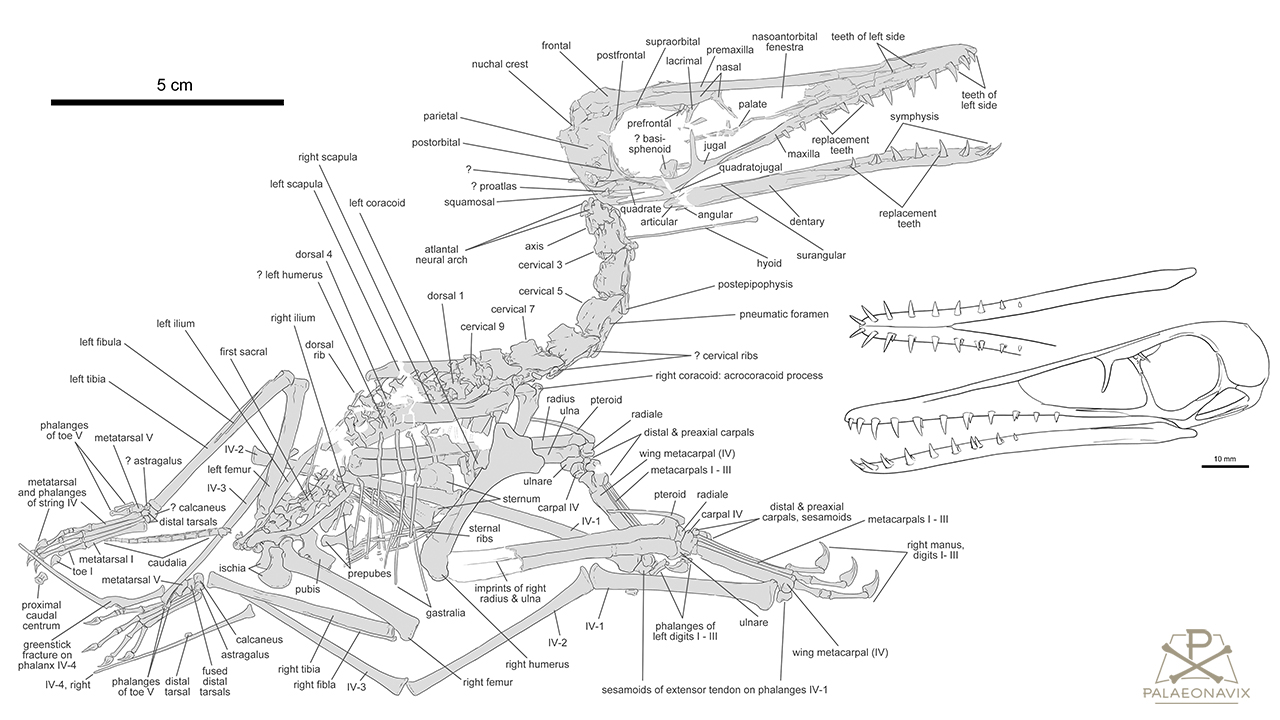

Starting in the late 2000s, some transitional forms became known, first from China, but also from Bavaria. Today, we have a rather consistent view on the pterodactyloid transition (while the morphological transition towards the first Triassic pterosaurs still represents the biggest riddle in tetrapod evolution!). From China, and in the meantime also Europe, the darwinopterans illuminate the skull elongation and initial shortening of tails. The steps directly preceding the origin of true pterodactyls are known from a few “Solnhofen” specimens. While the first one, the so-called “Rhamphodactylus” is currently prepared for publication, we managed to describe two others, in order to document the most complete anatomical sets first. These are Makrodactylus (skeletal diagram) and Propterodactylus (in situ drawing, skull reconstruction, and life restoration).

The common traits of such near-pterodactyls are an only initially elongated middle hand, rather short cervicals, an already short tail but with primitive vertebral interlocking, and a still present 5th pedal toe. From a higher perspective, this all looks perfect, like missing links on a straight line. Even the skulls resemble those of baby Pterodactylus. Looking more closely, slight differences in the proportions and dentition point to a radiation of a formerly unknow type of pterosaur, not just steps towards pterodactyls. At the time when Makrodactylus and Propterodactylus lived, the pterodactyloid transition was at least 15 million years in the past. Therefore, these connecting links can only indirectly represent the morphological pathway from their more primitive to their more derived relatives. Still, they seem so intermediate like they were designed (or dreamed up) by a palaeontologist.

Spindler, F. (2024): A pterosaurian connecting link. from the Late Jurassic of Germany. Palaeontologia Electronica, 27(2): a35. https://doi.org/10.26879/1366

Hone, D.W.E., Lauer, R., Lauer, B., & Spindler, F. (2025): A new non-pterodactyloid monofenestratan pterosaur from the Mörnsheim Formation of southern Germany. Palaeontologia Electronica, 28(3): a42. https://doi.org/10.26879/1543