Biocrusts: Earth’s history, but from the ground perspective

digital paintings, 2014

more on lichens & algae / see another concept of subsoil time spirals

If you look at a timeline or a time spiral, you often come across dinosaurs, perhaps an ammonite, and in any case a man at the end. We are focused on ourselves, in the next instance on other vertebrates, then animals. But only large animals. The paramount role of arthropods is already lost, even more so that of plants. A chronology of plants would be just as interesting, and much more important in terms of ecology. Then the focus would not be so much on the end of the Cretaceous period, but rather on its beginning. The modern flora is a product of the Cretaceous period, only the large fauna and primarily on land is the foundation of the Cenozoic.

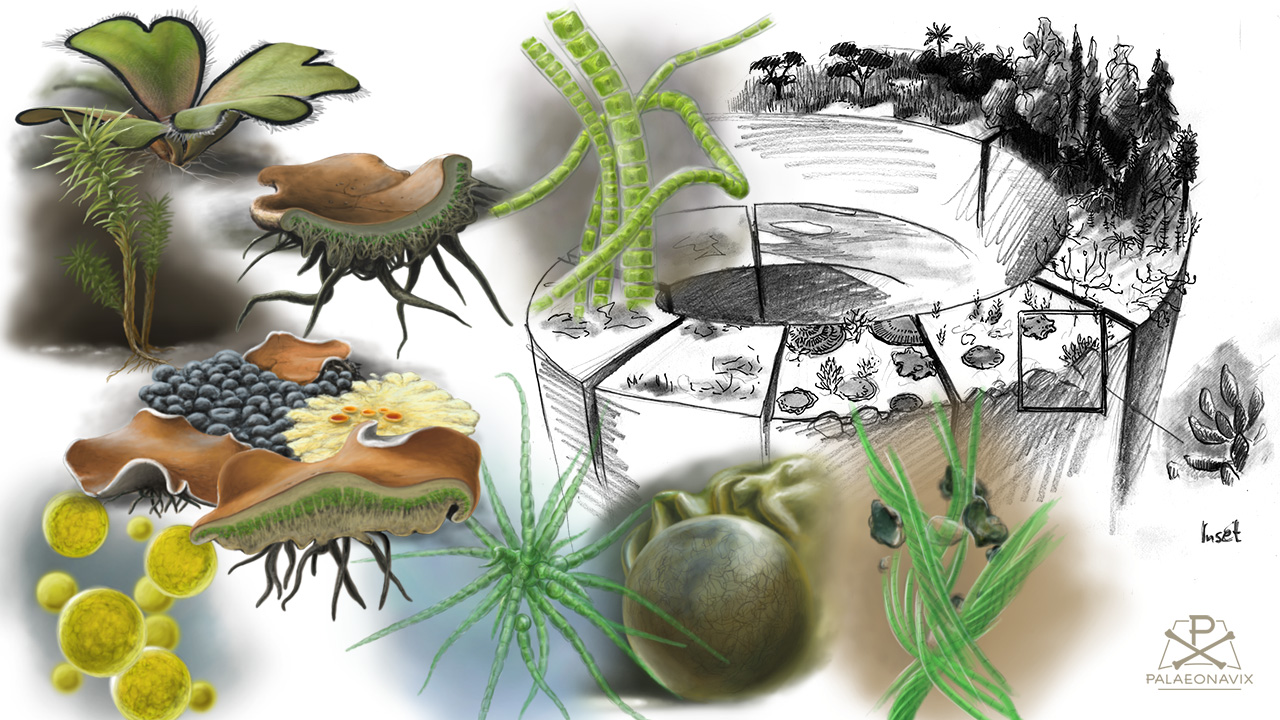

This illustration goes one step further from the classic inventory: it shows the evolution of biocrusts (biological soil crusts), i.e. an ecological guild and significance rather than a specific group. Plants are of course involved, but rather marginally and late. Precise time control is difficult anyway, because the fossil record here is based on incomplete finds or chemical residues. Soils in general are a rather short-term affair, on the scale of geological eras. And they would change quickly in their biological composition, both living and humus, within the conservation processes. That is why this picture is part of a research front that deserves much more attention.

Biocrusts are biological coatings on and in the soil, but also on other hard substrates, such as stones and rock faces, tree trunks or buildings. The majority of these living films are photosynthetically active. Of course, the proportion of global oxygen production does not come close to that of grasslands, forest belts or, above all, oceanic phytoplankton. Nevertheless, we owe a few percent of oxygen to these sometimes unsightly and yet vital plaques.

The first large-scale oxygen producers were cyanobacteria, whose encrusting layered structures (stromatolites) have been changing the atmosphere in our favour for 3.5 billion years. Bacteria and archaea, the two actual domains of life, were probably interested in the coastal zone early on, where air and water meet and all kinds of exciting microhabitats emerge. To this day, there are other growth forms in addition to the filamentous cyanobacteria (first miniature). Among them, Nostoc forms coiled layers and tubes, some even spheres (second miniature). They occur worldwide in fresh water, but also in damp niches on land. Sometimes it is the edge next to a park bench or in the cracks of a manhole cover where the slimy-looking squiggles grow. It sounds like a cliché, but in China they are even eaten as vegetables. Bacteria are not always microscopic, but as such colonies are also quite saladable.

Eukarya, i.e. organisms with a cell nucleus, emerged from Archaea through endosymbiosis with certain bacteria. When they integrate cyanobacteria, we speak of chloroplasts, and the entire life form turns into a eukaryotic alga. The term algae covers a wide variety of life forms, with very different relationships, primarily unicellular, often multicellular. Both cyanobacteria and nucleus-bearing algae were increasingly conquering the dry land and thus also the substrate depths (up to the center of the picture). As much as they need light to run photosynthesis, they also need moisture and space to live. The surface is highly competitive and can dry out quickly. Extreme habitats offer a way out with little competition.

Among the eukaryotes that have never achieved photosynthesis are fungi (and no, fungi are not plants, they are more closely related to animals and have developed their multicellularity independently). Now, integrating cyanobacteria or cells that already contain them in the form of chloroplasts is not the only way to bring photosynthesis into one's life. One of the most successful solutions is the integration of unicellular algae, cyano-bacterial or eukaryotic, but not within their own cells, but between them and in spongy cavities in the tissue. Fungi that achieve this become lichen, a closely symbiotic life form (miniatures to the right of the center of the picture). The enveloping fungus provides space, protection and moisture. The algae provide sugar, the tasty and energy-rich output of photosynthesis. In dry times, the entire lichen survives on a low flame. When it gets damp, it swells up again and revs up its metabolism.

In the logical order of colonization by biocrusts, it was assumed that lichens must have existed for a very long time. The preconditions were all in place even before plants developed. This happened in such a way that a certain branch of multicellular green algae (Streptophyta) first gave rise to various land forms, which we summarize in the broadest sense as mosses (miniatures on the right), and finally to vascular plants. Recent findings suggest that these origins of the plant kingdom are older. Firstly, because plants probably originated in the Cambrian, far older than previously assumed. Secondly, because the evidence of lichens from the Devonian or even the Silurian does not necessarily relate to today's forms or others may not have been larger land forms. The origin of lichens as we know them was probably not until the Jurassic!

Either way, the development of biocrusts is an essential prerequisite for vegetation and subsequently also animal life on land. With the spread of grasslands in the late Cenozoic, the world of soils and biocrusts changed once again, but the fundamental and shaping role has essentially been the same for billions of years. Without biocrusts it does not work, and would not work any longer.