Edaphosaurids, sail-backed herbivores rare in Europe

ink stippling and digital, 2019; all artwork by Freddi Spindler

Edaphosaurids belong to the ‘pelycosaurs’, early synapsids and thus the first representatives of the mammalian line, shortly after the separation from the reptilian line. It is therefore hardly surprising that they superficially have these iguana-like proportions, because so much evolution towards true mammals has not yet taken place. The common ancestor with reptiles is thought to have lived around 320 million years ago. Just about 15 million years later, there were clearly recognisable Edaphosauridae. Clearly recognisable here means: dorsal sails made of elongated spine processes. Unlike the carnivorous Dimetrodon, the long bone rods also had lateral spikes (in nearly all edaphosaurids), which may have served to ward off predators. This is not certain, however, as is the whole question of the function of dorsal sails.

Edaphosaurus itself is an expectable genus in some sites in the southern United States. Five species are distinguished, which grew larger and larger from the end of the Carboniferous period to the end of the Early Permian, reaching a total length of over 3 metres. In addition to a few other genera with little fossil evidence, there are several finds of Ianthasaurus, a rather primitive genus. While Edaphosaurus was a sophisticated plant eater for its time, and the other edaphosaurids share similar adaptations, Ianthosaurus seems to have preyed on animals, at least during its young stages. Overall, this paints a nice and understandable evolutionary picture that sheds light on this geologically oldest group of fibre eaters. And it all appears to have taken place almost exclusively in North America.

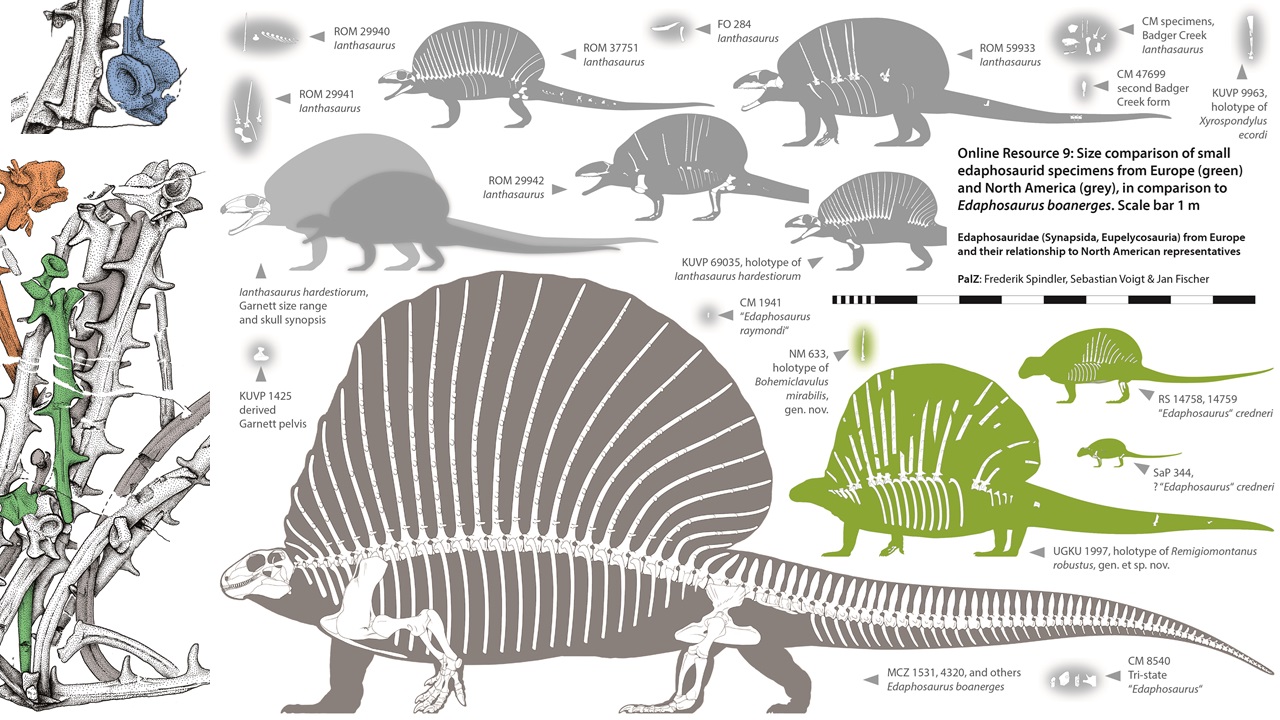

A few years ago, a somewhat chaotic but structurally well-preserved edaphosaurid spine was discovered in Germany. Its age is around the Carboniferous-Permian boundary, which means it is already from the time of Edaphosaurus species, but still early enough to provide further insights into the evolutionary history of the entire group – at least that was our hope when we began the study. First, the whole bundle of elongated spines had to be untangled, a kind of virtual mikado. A close-up of this can be seen on the right of the figure. The result was the (so far) most complete find of a bigger edaphosaurid in Europe and indeed outside the USA. Based on a few deviating details, we were able to classify the fossil outside the genus Edaphosaurus. We named the new genus Remigiomontanus, after the Remigiusberg quarry where it was found. The largest of the green skeletons in the figure shows what is preserved. The few toes have since been confirmed as a mistake, so what remains is a set of neck ribs, rib cage and lumbar ribs, enough of the back for a solid reconstruction of the sail, and very few tail vertebrae. In terms of anatomy and size, it is a perfect ancestor of Edaphosaurus, without any special features (autapomorphies). For comparison look at the big grey one: This is the best-known Edaphosaurus, and not even the biggest.

We took the study as an occasion to examine all edaphosaurids from Europe (in green). There are not many of them. A fragment of a sail cannot be identified, but surpassed Remigiomontanus in size (not depicted). There are two babies, one with an almost adult-looking dorsal sail (which rules out signalling for sexual selection as its primary function). The other shows a skull bone that clearly points towards Edaphosaurus. The oldest find in Europe, both historically and geologically, consists of a single vertebra. Since several details differed from Ianthasaurus, a new genus was suggested. One could argue whether this makes sense based on a single bone. However, since several names were circulating for the piece, the question of whether it should have a scientific name at all was already anticipated. The new genus Bohemiclavulus was quickly adopted by the National Museum in Prague, where the original and a fairly good sculpture of this primitive edaphosaurid are on display.

The grey remainder represents known Ianthasaurus individuals and similar material. This was necessary because, firstly, no such overview existed, and secondly, to learn about the spectrum within the genus. Ianthasaurus certainly exhibits variability, including growth-related deviations. Not everything about it has been fully explained yet. Proving Bohemiclavulus was definitely worth the effort. The bottom line is that Ianthasaurus is not quite the ideal ancestor of the Remigimontanus-Edaphosaurus lineage. It is already the origin of all edaphosaurids that seems to be more complicated than just evolving this sail type and then leading to Edaphosaurus by straightforward trends.

Apart from the different fossil records, we cannot identify any significant differences between America and Europe. A well-connected distribution area probably extended across the ‘Permian-Carboniferous’ tropical swamps.

This story continues, because in the foreseeable future Remigiomontanus will join the league of the truly well-known pelycosaurs.

Spindler, F., Voigt, S., & Fischer, J. (2020): Edaphosauridae (Synapsida, Eupelycosauria) from Europe and their relationship to North American representatives. PalZ, 94(1): 125-153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12542-019-00453-2