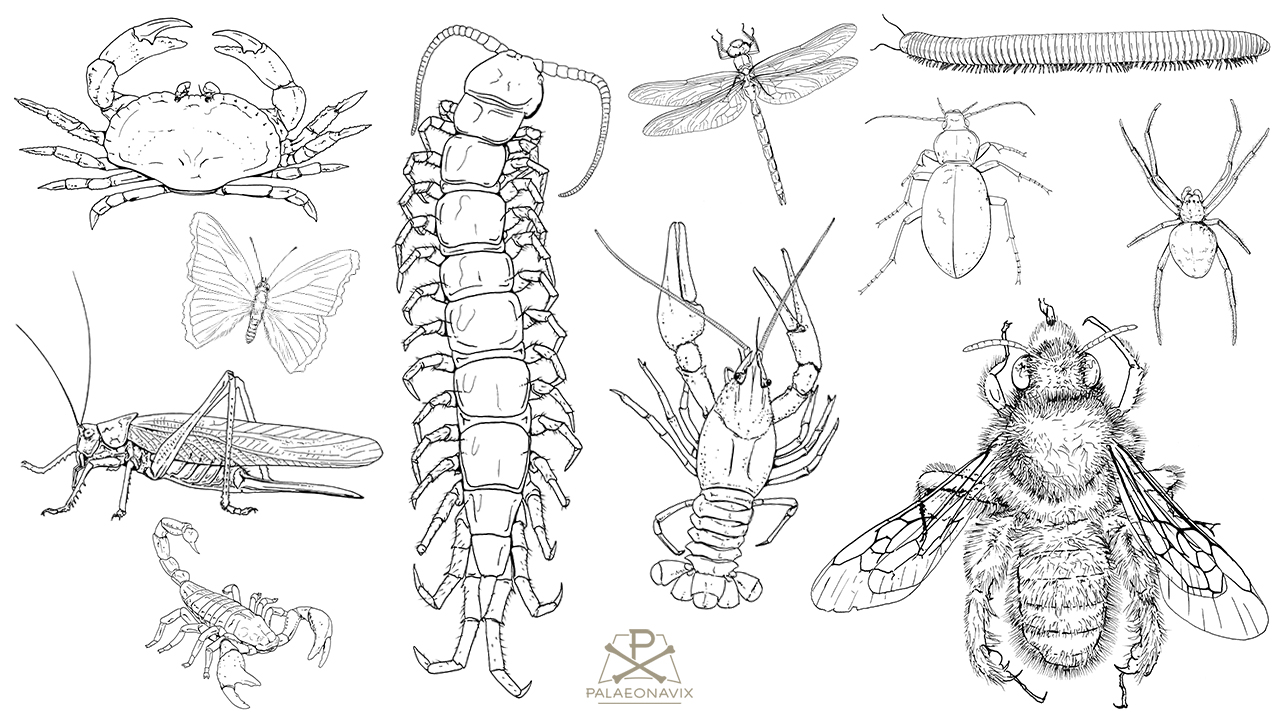

Arthropods: it's their world, we merely inhabit it

ink drawing, early 2010s

Museum für Naturkunde Chemnitz, Saxony

This whole concept of defining ranks for groups of organisms has long since failed. How is the subphylum of shell-bearing molluscs = Conchifera supposed to know that it contains the same degree of similarity and disparity as the subphylum Vertebrata?! We are faced with the systemic problem that similarity cannot be measured, not even approximated, as features cannot ultimately be counted or assumed to be equivalent. And yet, sometimes the significance of a group is so clear that its unity is more than just a collective term. The outstanding success of the Arthropoda is based on an anatomy and physiology that actually makes them superior to other “phyla”. This status has probably remained unchanged for more than half a billion years, which is almost the entire history of multicellular life since the Cambrian radiation around 540 million years ago.

We can only provide reliable estimates of species numbers for the present time. Accordingly, arthropods are the clear winner with over 80 percent of all animal species. Insects are of course the mainstay, with well over a million species. Their ability to fly gives them a huge advantage, especially as arthropods are, with a few exceptions, small. This may seem like a disadvantage to some, simply because we as humans are a rather large species ourselves and are impressed by the appearance of elephants or T.rex. The exoskeleton, on the other hand, sets biomechanical limits on the ability of many animal species to support their own body weight and maintain sufficient mobility. This means that palm-sized beetles are already giants and close to the limit of what is possible, at least on land. However, this circumstance puts arthropods in an ecological role in which they produce considerably more individuals and ultimately account for more biomass than vertebrates, for example. Add to this increased evolutionary rates, great resilience and such factors, and everything is clear. We live on an arthropod planet or insect planet. Bugs form the dominant bauplan in the animal kingdom, precisely because they are not sensitive big players.

Arthropods are a difficult case in pictorial representation, especially in palaeo-illustration. On the one hand, well-preserved fossils can barely be reconstructed, i.e. their external appearance is fixed as soon as the exoskeleton of a body or organ is well preserved. On the other hand, this great precision is quite exhausting. Each segment has a fixed shape and positional relationship to adjacent armor parts. The positions of hairs are often precisely defined, as are the compound eyes or – and now we are talking about visible, highly diagnostic features – the wing veining, the gill bristles, claws and hooks on the legs. In other words, it's not quite as easy as a wobbly squid or a fossil reptile, where deviations and room for imagination simplify the task.

Lucky for me, this commission was about extant arthropods, so I was able to use exact reference models. Nevertheless, I didn't want it to be just a simple redrawing of photos. The result is worth seeing, and the line drawing by hand conveys the robot-like nature of the arthropods quite nicely. So, what do we have here: a brown crab, a butterfly, a bush cricket, a scorpion, a scolopender, a dragonfly, a millipede, a ground beetle, a garden spider, a crayfish, and finally the honeybee as the symbol of importance for us humans too. Because when environmental campaigners point out that we are triggering an insect extinction (and this is so definitely exclusively man-made!) like there has not been an extinction since the decline of the big dinosaurs, then this is no exaggeration at all. Since the early Cretaceous period, pollinating insects have been so vital to the ecology on land that their crisis could make everything discussed about climate change worse. And speaking of which: Many arthropods will definitely benefit from climate change, just not necessarily the ones we like.