Tetraceratops, the bizarre, horned pelycosaur

digital painting, 2020; all artwork by Freddi Spindler

learn more about early types of Sphenacodontia / a possible early therapsid is Pantelosaurus

I found the genus name Monoceratops in a scientific article – but it's probably a typo; apart from that it's apparently a topic for fictional palaeontology (how people spend their time...). Also, Diceratops is no longer a dinosaur name since it was preoccupied by an ichneumonid wasp. The new name Nedoceratops may also be discarded if it proves to be simply a variant of Triceratops. The latter is, of course, valid, and every true dinosaur fan knows the translation of its name: three-horned face. Pentaceratops, also a horned dinosaur (Ceratopsidae), even counts to five. So where is number four in that line?

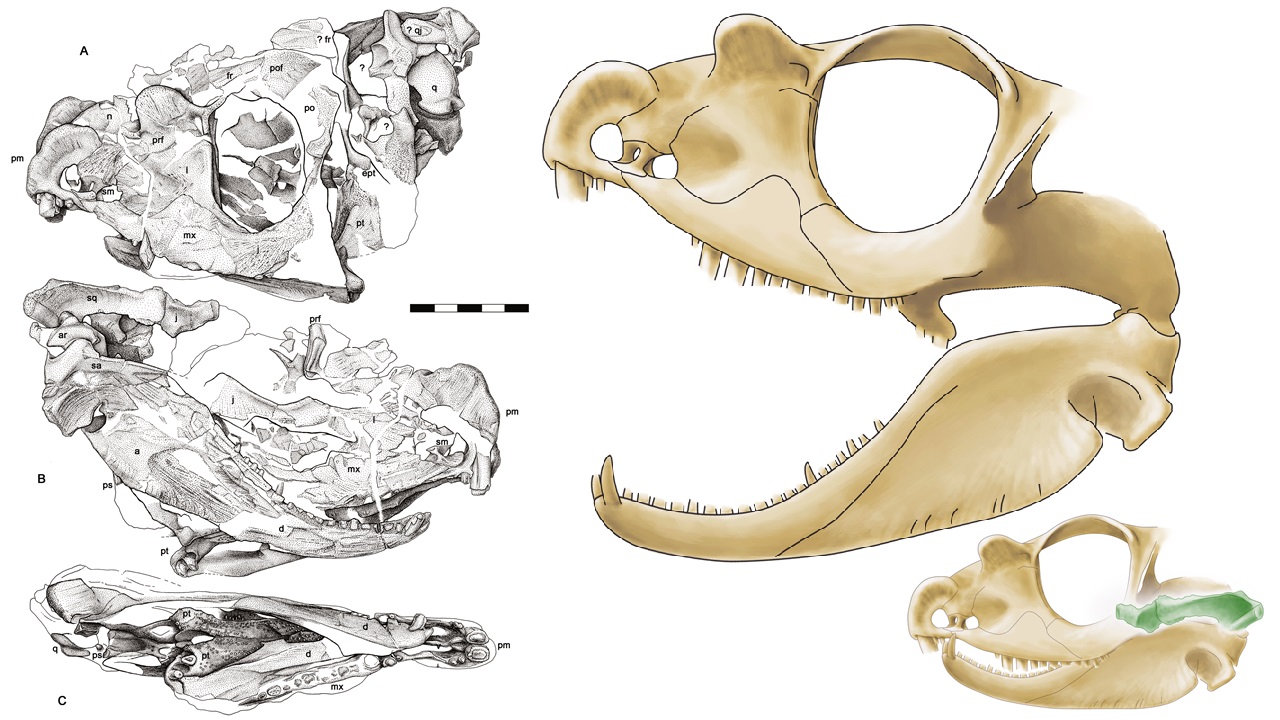

The four-horned face, Tetraceratops, was already named back in 1908. This time it is not a dinosaur, but a pelycosaur. Only a single, badly crushed skull has been found. The dental margins, large eye sockets, the outline of the lower jaw, a strikingly short snout with two pairs of bumps on the roof are clearly recognisable. There was never any doubt about the uniqueness of this critter. Although its proportions appear totally weird, enough anatomical details are visible to classify it as a sphenacodont, i.e. within the early synapsids, very close to the origin of recognisable mammalian ancestors. Comparisons have been made with Dimetrodon, for example. Stratigraphically, this fits perfectly, namely addressing the upper part of the Lower Permian. To this day, it remains unclear whether it even had a small dorsal sail – no one has drawn it yet, but it is entirely conceivable...

In the 1990s and 2000s, there was a long-held and unchallenged view that Tetraceratops was the oldest known representative of the therapsids. These are also sphenacodonts, but they leave the early field of pelycosaurs. Therapsids became dominant in the Middle Permian and showed significantly more ‘mammalness’. Formally, they also include mammals, which means that you and I are in fact therapsids. Due to their relationship with certain pelycosaurs such as Dimetrodon and Sphenacodon, the therapsid lineage undoubtedly split off in the late Carboniferous period. The prediction is therefore that they existed during the early Permian period, but no one knows how therapsids looked at that time, or when they left the morphological spectrum of the still very reptile-like pelycosaurs. This therapsid transition mainly brings more upright limbs, something to which Tetraceratops, with only a skull, could make little contribution.

Classifying Tetraceratops as a therapsid was very influential because it began to bridge what was perhaps the largest gap in our knowledge of Paleozoic tetrapods [or comparable with the ancestry of modern amphibians, or Romer's gap regarding early tetrapods]. The decisive argument was the observation that Tetraceratops had a widely extended temporal window with a broad rim. This opening behind the eye, where the chewing muscles were located in life, is relatively monotonous in synapsids: there is one opening on each side, outlined by fairly the same skull bones. There are deviations, but not nearly as wild as in the evolution of early reptiles. Even mammals retain roughly the same simple temporal fossa, except that the inflated braincase gives it a different look. In pelycosaurs, at least, the temporal window is usually small and evolutionarily conservative, up to and including the first sphenacodonts such as Dimetrodon and Sphenacodon. After the great leap in time and morphology towards the therapsids, i.e. the even more mammal-like sphenacodonts from the Middle Permian onwards, the skull window was enlarged and often surrounded by a broad margin. This means that the bite force had increased considerably during the therapsid transition. Finding this in Tetraceratops actually leads to the sensational insight that an early Permian therapsid has been identified.

I had the incredible luck to be able to study this skull. Since I was researching the origins of therapsids, I naturally followed the renowned colleagues, wanting only to gain my own impression through detailed drawing and perhaps tease out a few more details. Drawing it from three angles was a real challenge. It turned out that previous depictions had been embellished, guided more by an idea than by openness to the fossil. Also, there was something wrong with the rim around the temporal opening. The bar in question is detached from the rest of the skull and clearly shows a strong muscle attachment for a very powerful bite. However, the pattern of deformation does not match the rest of the skull if this bar is to be placed at the upper edge of the temporal window. The entire fossil is severely deformed and shows compaction in exactly one direction – actually something very normal in sedimentary rocks that are compressed under the growing load of ongoing deposition. However, the crucial bone bar would require the skull roof to have folded in the opposite direction compared to the remainder bones. But that would be a totally artificial, physically impossible movement. Then other parts of the temporal region would also need to align downwards, but they don't. Instead, the components of the jaw joint are exactly where they should be according to the analysis of compaction.

So what happened? There was a good anatomical observation and a solid classification within the known spectrum: the broad margin looks like the temple of a therapsid, so it is a therapsid. Unfortunately, only anatomy was considered, but not taphonomy, i.e. studying the processes between the death of poor little Tetraceratops and its recovery as a fossil. When most palaeontologists look at taphonomy at all, it is because they learn something about the environment and behaviour. The observation of diagenesis in the embedding rock is of no interest to evolutionary researchers. Nevertheless, this view was necessary here. The cryptic bone bar does not come from the upper edge of the temporal fossa, but is a slightly twisted and correctly placed zygomatic arch. The key argument for a therapsid classification was a simple mistake.

There are also sutures on the face that are reminiscent of the origins of therapsids. However, all phylogenetic analyses show that the direct relationship between Dimetrodon and its kin (‘still-pelycosaurs’) with therapsids is based, among other aspects, on the fact that the lacrimal bone recedes from the nose. However, this bone between the dental margin and the horns, longitudinally between the nostril and the eye, has exactly the same extension as in slightly more primitive forms, such as Pantelosaurus and Palaeohatteria. The lacrimal bone receding from the nose may, of course, have developed independently in therapsids and Dimetrodon/Sphenacodon, but this has not yet been conclusively proven. A reaction to the conspicuously shortened snout in Tetraceratops would also lead to a short lacrimal, so it is not an exceptional reversal in this genus.

All in all, Tetraceratops continues to play an important role in the still very hypothetical ideas about the therapsid transition. My pelycosaur-grade classification of Tetraceratops was also discussed for a while – it may be so, but may be different. But as long as the compaction patterns are taken into account, no therapsid conditions of the upper temporal region are detectable. It is simply not known because it has not been recovered. By now, many accept this assessment. Nevertheless, I believe that we are still imagining some things too simply when it comes to the origins of therapsids.

And what about the horns? I argue and substantiate that Tetraceratops is a ‘pelycosaur,’ i.e., a non-therapsid. This makes it the only known case of such skull ornamentation in pelycosaur-grade synapsids. Among Middle and Upper Permian therapsids, many different types of humps and horns are known, presumably due to an increase in social signalling. This function cannot be ruled out for Tetraceratops either. I would like to propose an alternative, albeit rather speculative, idea: what if the bumps were used for digging rather than for impressing others or wrestling? There are parallels in some mammals – read the publication.

Spindler, F. (2020): The skull of Tetraceratops insignis (Synapsida, Sphenacodontia). Palaeovertebrata, 43(1): e1. https://doi.org/10.18563/pv.43.1.e1