Sphenacodontian-type predators

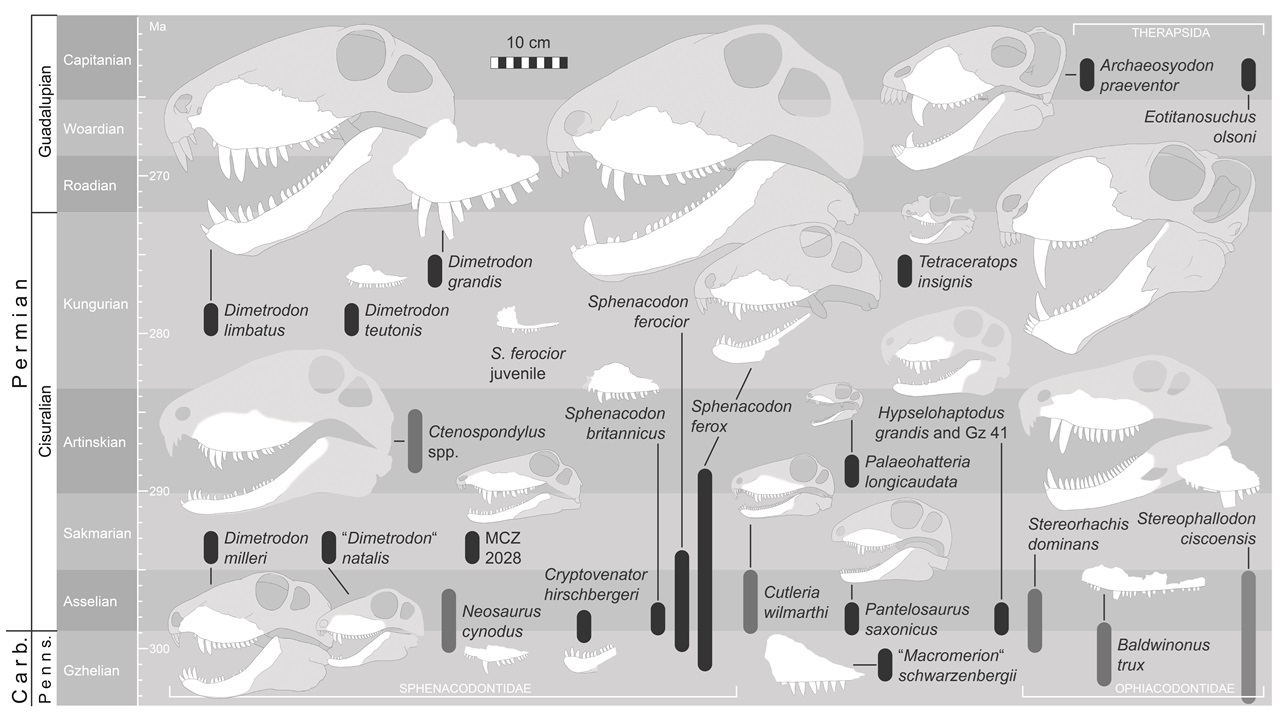

digital drawing, 2019; all artwork by Freddi Spindler

the weirdest early sphenacodont was Tetraceratops / learn more about Pantelosaurus

Early synapsids are those precursors of mammals whose relationship to mammals is not yet apparent. The fact that they were previously classified as reptiles was partly because tree thinking was not yet widespread. Secondly, it was because they were still close to their common origin with reptiles. It is anatomical features in the dentition or temporal region, for example, that reveal synapsids as mammalian ancestors. Those that looked more like big lizards are known as pelycosaurs, some of which are famous for their tall back sails.

The pelycosaurs with the closest relationship to mammals are the sphenacodonts. Such inconspicuous, featureless genera like Pantelosaurus and Palaeohatteria actually represent the stage of our own ancestral line when we last looked like a fat monitor lizard with very little of a neck. Perhaps the most famous are the sphenacodontids, apex predators from the early Permian period such as Dimetrodon. In fact, there is a whole range of different skulls behind this name, and the bizarre long-snouted Secodontosaurus is not even included here. If you imagine the back sail absent or significantly lower, you end up with Sphenacodon or Ctenospondylus.

The Therapsida evolved in a different direction from the Sphenacodontidae. Therapsids are usually defined as moderately mammal-like synapsids, but formally the term also includes mammals and thus humans. They are all Sphenacodontia that can no longer be referred to as ‘pelycosaurs’. In their most primitive form known to us, they had strong canines and enlarged temporal fossae (the holes behind the eyes that reveal something about the dimensions of the chewing musculature). We can imagine these early therapsids of the Middle Permian to resemble Archaeosyodon or Eotitanosuchus.

The only problem is that Dimetrodon and other sphenacodontids first appeared in the late Carboniferous period. Since all analyses agree that they are closely related to therapsids, the latter must also be just as old. Let's be precise: they are just as old, which is a clear prediction. This means that therapsids are entirely missing from the early Permian period.

Or they are there, but so rare and so primitive that they are anatomically hidden from us. It is also unclear when they underwent the morphological therapsid transition. There are individual characteristics in Pantelosaurus and Palaeohatteria that look suspiciously like therapsids. Perhaps this reflects the therapsid appearance during the early Permian, which is not more primitive than the sphenacodontids in terms of phylogeny, but simply their sister group at an early stage. This overview was created for a new description of Hypselohaptodus, which is also somewhat more complicated than was thought decades ago. If such forms are believed to be therapsids, this would make sense in bridging one of the longest ghost lineages in the evolutionary research of tetrapods.

A second problem is that the Ophiacodontidae also want to play a part. This family of pelycosaurs is significantly more basal than the entire Sphenacodontia stage. But they should not be reduced to the (presumably fish-eating) forms around Ophiacodon. Stereorhachis and Stereophallodon show adaptations to a hypercarnivorous lifestyle. As a result, they became quite similar to some sphenacodonts due to convergent evolution. So, in the end, it may become difficult to classify fragmentary finds within this spectrum.

Spindler, F. (2019): Re-evaluation of an early sphenacodontian synapsid from the Lower Permian of England. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 111: 27-37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175569101900015X